In the Diamond Mountains :

Adventures Among the Buddhist Monasteries of Eastern

Korea

By the Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

Where every prospect pleases

And only man is vile.—Bishop Heber.

[The journey was made in October 1892 but this account

of it was published in the National Geographic

Magazine of October 1924, together with some 20

photos, of which only a very few have the Diamond

Mountains as their subject, and they seem to be from

various decades.]

In the course of my travels I have come

across a good many monks and monkish communities and

have spent nights of interest, though hardly of luxury

and not always of repose, in monastic guest chambers or

cells.

I have walked in pilgrimage round the

pyramidal spires of Monserrat; have been hauled up in a

net to the eyries of Meteora; have dined with the abbot

of the great monastery of Troitsa, near Moscow; have

fraternized with the dwindling Greek fraternities of

Athos; and with the more prosperous Russians on Tabor;

have sojourned in the grim monastery of Mar Saba, near

the Dead Sea; was once rescued with difficulty, and only

by the tact and savoir-faire of my companion, Sir John

Jordan, from the menacing approaches of the Lamas in the

great Tibetan monastery at Peking; have addressed an

audience of 2,000 yellow robed Burmese monks at

Mandalay, and have slept at night on the polished temple

floors of the monasteries of Korea (Chosen).

I shrink, even after this rather

diversified experience, from generalizing about monks,

since I have found them divided, like other classes of

mankind, between saints and profligates, bons vivants

and ascetics, gentlemen and vagabonds, men of education

and illiterate boors. But of all my monastic adventures

I think that the ones which linger longest in my memory

are the days that I spent with my friend, the late Cecil

Spring-Rice, afterwards British ambassador at

Washington, in wandering among the monasteries of

eastern Korea.

And the reasons for my preference are

these:

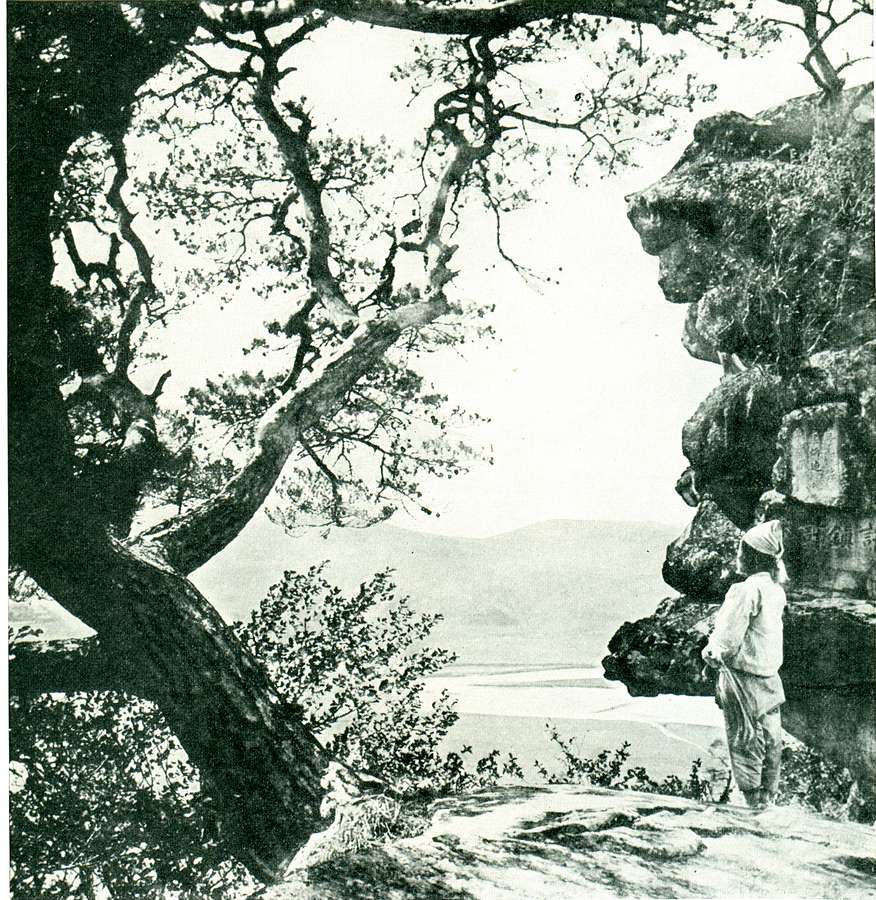

First, the scenery amid which these

monastic retreats are hidden is among the most

enchanting in the East. Indeed, it may fairly be

described as one of the little known beauty spots of the

world.

Secondly, there was not the faintest

masquerade of piety among the great majority of these

rather seedy scamps, some of whom were quondam criminals

of the deepest dye; and this invested them with an

originality which, if not admirable, was at least

piquant.

And, thirdly, I had the supreme

satisfaction of arresting an abbot and carrying him off,

a captive of my bow and spear.

Doubtless other European travelers after my

day have threaded the picturesque gorges of the Diamond

Mountains; and, for all I know, since the vacuum-cleaner

of Japanese rule has sucked out the dust and dirt from

the crannies and corners of the dilapidated old Korean

tenement, the monasteries may by now have been

expurgated and the monks made respectable, and a road

for motor cars driven to the threshold of the Keumkang

San. But as I was one of the earliest Europeans to visit

those exquisite retreats. now 32 years ago (October,

1892), it may be worth while to set down a few of my

memories of the scene as it was in those unregenerate

days of mingled rascality and romance.

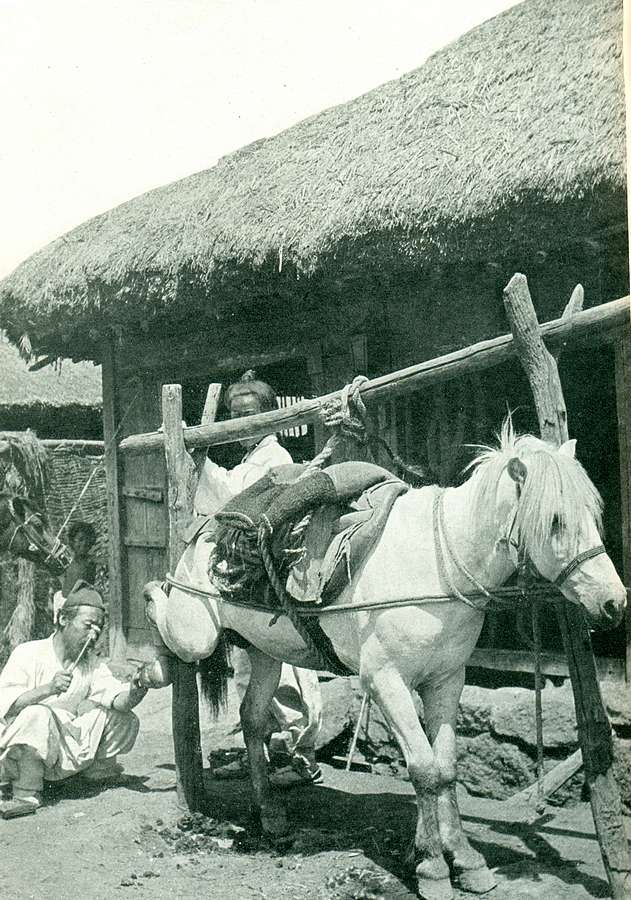

In my book on Korea I described the

incidents and features of travel as I saw them in that

singularly backward and unsophisticated country—the

little, sturdy, combative ponies; the garrulous,

quarrelsome, lazy pony-men, or mapus; the

indolent, strong-limbed people; the picturesque variety

of scenery, the perfect climate, the abundance of winged

game, the torchlit marches at night, the total absence

of roads, the incredibly disgusting native inns.

J. B. Millet

J. B. Millet

The "Eunjin Mireuk" in Gwanchoksa temple near Nonsan

is the largest stone Buddha in Korea. It represents

the Buddha of the Future.

Travelling to the Chief Monastery

of Korea

It

was amid such surroundings that my acquaintance with the

Korean cloister was made. We were marching from Wensan

or Gensan, a port on the eastern coast to the capital,

Seoul (Keijo), a distance of 170 miles; but we deviated

from the familiar track (which a railway now nearly

parallels) to visit the monasteries to the east of the

road.

It was soon after passing Narnsan, 15 miles

from Wensan, that we left the plain and plunged into the

interior of a wooded range. the crimson of whose

autumnal maples and chestnuts burned like a dying flame

against the sky.

Our destination was the monastery of

Syekwangsa, the chief or metropolitan monastic

establishment in Korea, founded about 500 years ago,

which I have not seen mentioned in the itinerary of

other travelers.

The bridle-path—for no road in Korea at

that time was any more or better—followed the windings

of a sylvan glen, down which brawled a mountain stream.

On either side were rocks on whose chiseled surface

centuries of pilgrims had inscribed their names in bold

Chinese characters.

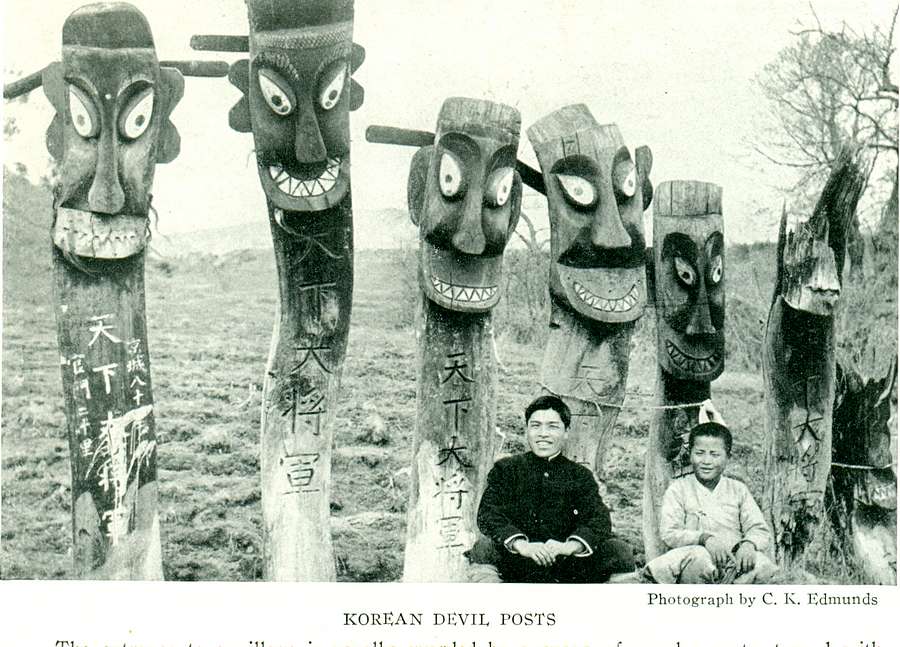

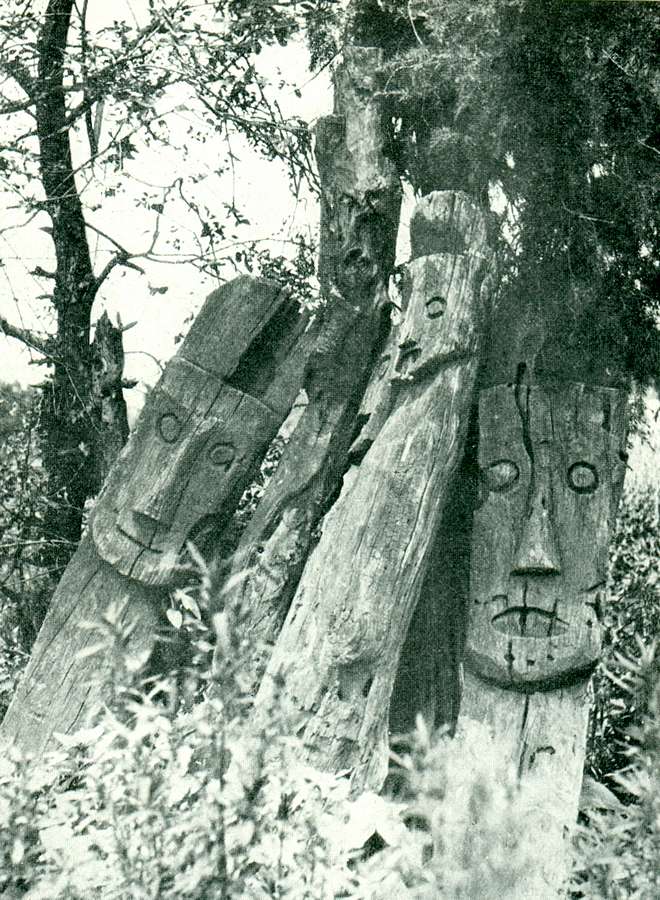

In turn we passed the cemetery of the

monks, marked by lanternlike pillars of stone, heavily

eaved resthouses built for visitors, and a series of

hideous painted wooden posts, each terminating in a

grinning head, erected to ward off the assault of evil

spirits. [*The theory is that all Nature is pervaded by

spirits and genii, who require to be propitiated and,

when malevolent, to he kept aloof.]

So we came, as the track broadened, to a

hollowed amphitheater, which seemed to have been scooped

out for the purpose in the hillside, where, on terrace

above terrace, stood the monastic buildings.

Curzon

Curzon

Seo-gwang-sa temple near Wonsan. Completely obliterated

by a 1951 US bombing

A Night with the Monks

It was near midnight when we arrived and

presented our letters of introduction to the abbot. He

showed us our quarters, and there we cooked and ate our

meal, before the whole company of monks, in an

atmosphere which might have been cut with a knife, not

getting to bed till two in the morning.

.

Our sleep was on a floor stretched with

oiled paper, as smooth and shining as marble : in the

middle stood an altar and a Buddha behind glass.

Daylight had not dawned before we were

aroused by the peripatetic tramp of an early monk,

tapping a drum and singing a lugubrious chant. Another

began to clap-clap upon a brass gong. Presently the big

drum on the platform over the entrance was beaten to a

noisy tune, and finally all the bells and gongs in the

establishment were set going at once.

We rose and dressed before an appreciative

crowd, who took an overpowering interest in our

equipment, and more particularly in our sponges and

binoculars.

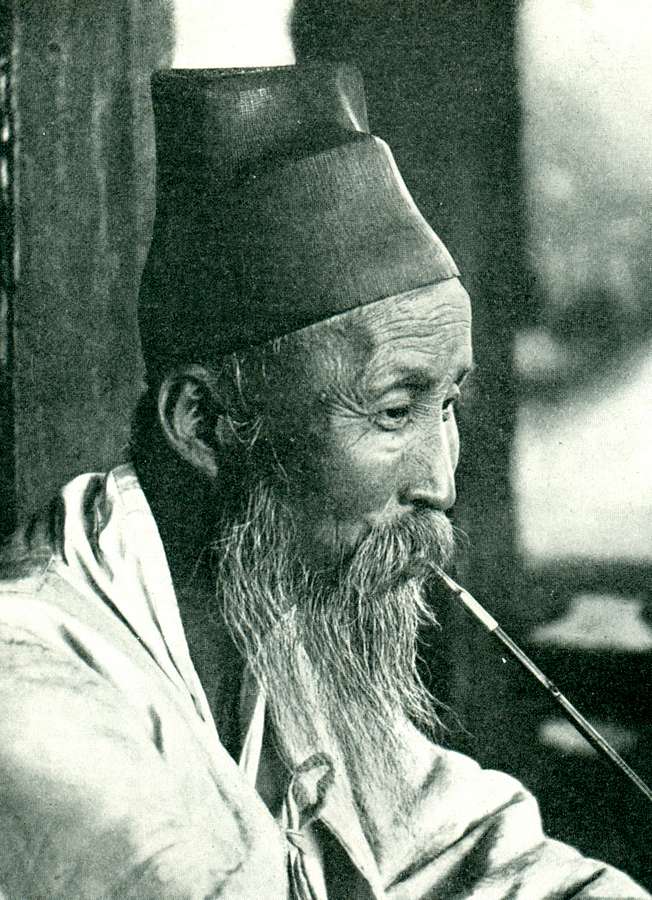

Then the worthy abbot. robed in a gray

dress, wearing a black circular horsehair hat, and

holding a staff in his hand, appeared to conduct us

around. His tiny eyes twinkled with good-humored

benevolence; a gray stubble sprouted from his unshaved

cheeks and chin; his big lips poured forth a voluble

flood in an unfamiliar tongue.

One temple at the side contained a hideous

painted wooden Buddha. A cluster of buildings to the

left of the entrance, terminating in a prayer platform

that overhung the torrent, was said to be reserved for

the King.

In the side court of the inclosure, looking

like a collection of little dolls with hoods were the

upper part of the painted stone figures of 500 Lohans or

Arhans—i.e., disciples of Buddha who were supposed to

have framed the Sacred Canon with him in India. These

images had a grotesque leer upon their whitened faces.

Curzon

Curzon

Jangan-sa temple in Geumgang-san

The Abbot Asks for a Double Fee

As we left, at 8:30 a.m., the good abbot

accompanied us to the gateway, and when I offered him

the paltry gratuity of one yen (50 cents) for the

night's hospitality, which I thought very shabby, but

had been enjoined at Wensan on no account to exceed, he

looked at the coin with an air of pained reproach and

murmured, "Couldn't you make it two?”

lt was quite impossible to resist this

pathetic appeal, my prompt response to which made him

quite happy and left me with the agreeable conviction

that human nature is much the same all the world over,

whether it be manifested in a London cabdriver or a

Korean abbot.

Anyhow, this excellent man stands forth in

my memory as the pleasantest and most human of all the

holy friars whom l was to see during the next few clays

of my wandering.

It was on the afternoon of the next day but

one that, leaving the main Wensan-Seoul track beyond

Hoiyang, we struck off eastward for our goal in the

Diamond Mountains.

The night was spent in the native village

of Sinhachang, where a rustic bridge of sticks and

shrubs, whose unstripped autumnal verdure made a ruddy

projecting fringe on either side, spanned a mountain

stream.

On the next day we climbed a pass to a

small shrine, or josshouse, which contained. amid a lot

of fluttering and filthy rags—the offerings of generations of

pilgrims—two pictures, said to be those of the King with

two boys, and the Queen with two girls.

A. M. Mirzaoff

A. M. Mirzaoff

The Dlamond Mountains are Sighted

But this was not the real interest. Before

us lay a view, not unlike, but more beautiful than, the

wild outlook in the Matoppo Hills as you climb to Cecil

Rhodes' burial place in South Africa. Four successive

ridges, like the palisades of some huge mountain

fortress, the walls of each stained crimson with the

heart's blood of the dying maple, filled the foreground.

Each must be climbed and each descended before the

splendid barrier of the Keumkang San, or Diamond

Mountains, fifth in the sequence, was reached. [*It is

uncertain whether the title is metaphorical, or refers

to the serrated outline of the peaks, or is derived from

the Diamond Sutra, one of the best known of the Buddhist

scriptures. The Japanese form of the name is Kongo San,

and they call the monastery of Chongansa (the Korean

form) Choanji.]

It could be seen, standing up beyond and

higher than its outer barricades, thickly mantled up to

its shoulders, above which a battlement of splintered

crags cut a fretwork pattern against the sky. Redder and

more red glowed the wooded slopes as the sun declined,

and an ashen pallor flickered on the granite boulders

and needle spires.

The last valley bottom was crossed, the

last river rushing down it in a rockstrewn bed was

forded; the main range, in its livery of crimson and

gold, was now in front of us.

C. K. Edmunds

C. K. Edmunds

Many Images and Effigies in the

Temple Inclosure

A lovely walk through a piny glade, past

monastic resthouses and under the scarlet archway, of

the Hong Sal Mun, or Red Arrow Gate, that is the

precursor of all buildings in Korea under royal

patronage, led to a cleared space, where, above the

rushing torrent, a cluster of buildings stood with their

backs to a wooded hill.

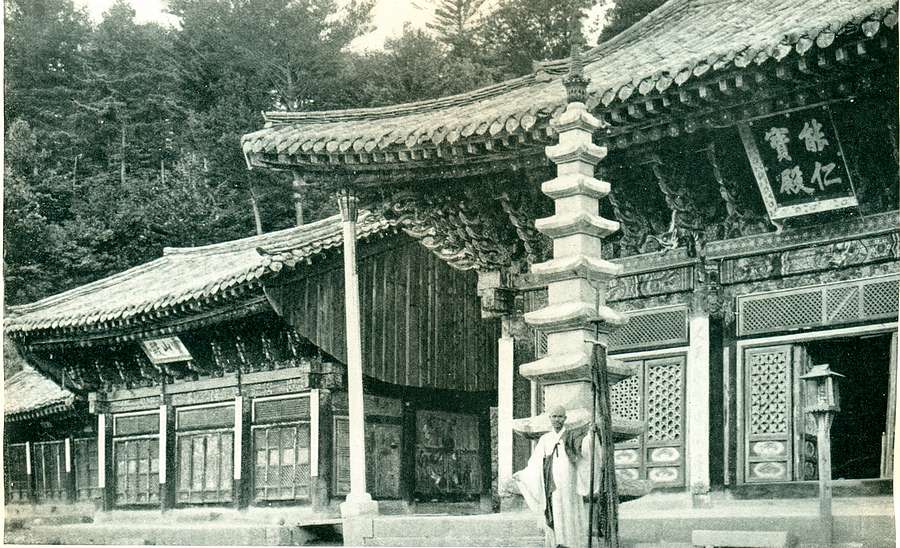

These were the halls of the Chongansa [*Changansa] Monastery, or the

Temple of Eternal Rest, the oldest and most famous of

the monasteries of the Diamond Mountains

First is an open-terraced gateway,

completely hung with tablets recording the names of

subscribers and containing a grotesque wooden monster

painted red, green, and white, representing one of the

sernideified heroes or warriors, genii or spirits, who

have been added in the passage of time to the Buddhist

Pantheon, overlaying it with a mass of demonolatry that

has well-nigh obliterated the original faith. A big bell

hangs in a sort of wooden pen adjoining.

Next we pass through a pillared chamber

into the courtyard of the monastery, at the head of

which stands the main temple with double-tiered roof of

tiles and deep overhanging tip-tilted eaves. The

guest-houses are at the side.

In the central hall of the temple a gilded

Buddha is seated in the middle on a raised wooden

terrace or platform painted red. Above his head is a

fantastically carved and painted canopy and in front of

his face is suspended a green gauze veil.

Six great wooden pillars, a yard in

diameter, formed of single tree trunk and colored red,

support the roof, which is painted in faded hues of blue

and green.

At the side of the hall is a painted scene

containing three Buddhas, in front of whom are colossal

images of warriors with diabolical faces.

Below the Buddhas, and indeed in front of

every Buddhistic image, is a low stool or altar with a

copy of the scriptures and a small brass bell, the

indispensable ritual accompaniments of service.

On the right of the courtyard stand smaller

detached temples containing other hideous effigies,

colored red, green, and blue; their faces are, as a

rule, painted white, and distorted with a horrible leer.

One holds his beard in his hand; another, a book; a

third, a scepter.

Small figures like boys are placed between

them, carrying images of animals in their hands. Round

are hung paintings on frames.

The second largest of these pavilions

contains a fine pagoda canopy over the seated Buddha and

a single row of figures seated and standing all round on

a raised terrace.

C. K. Edmunds

C. K. Edmunds

Yujeom-sa temple, Geumgang-san

A Bed of Korean Oil-Cloth Paper

Evensong began soon after our arrival.

A young monk pulled a gray robe over his

white dress and red hood, knelt on a circular mat,

intoned the conventional phrases, not one syllable of

which did he understand, struck a brass bell with a

deer's horn, and touched his forehead on the ground. The

act is one not of prayer, in our sense, but merely of

adoration.

We were accommodated in a guest hall or

temple, the floor of which was covered with the famous

Korean paper that glistened like worn oilcloth. We

unrolled our bedding at the foot of the altar, whence a

miniature Buddha smiled down upon us from a sort of

cage.

The monks—who had exhibited the liveliest

interest in our articles of toilet. particularly in

combs, nail scissors, and sponges, none of which had

they ever seen; still more in an inflated India-rubber

cushion, and most of all in a mouthplate of false

teeth—retired at 7 p. m. and left us to ourselves.

In the morning we saw the pad-marks and

droppings of a tiger, which had entered the courtyard

during the night and paced around the closed buildings.

Why he had been content to do no more, no one could say.

The jungles of northern Korea abound in these animals,

which levy an ample toll on animal and human life (for

many are man-eaters) and are pursued by guilds of

hunters with primitive weapons or caught in traps and

pits.

Here let me say a few words about the

Korean phase of monastic life, the last resorts of which

I am now describing.

It was in the early centuries of our

Christian Era that Buddhism made its way, it is alleged,

from India, but much more probably from China, into the

Korean peninsula. There in time it became not merely the

official cult of the royal and ruling classes, but also

the popular creed of the people.

Royal personages came on tour to the

monasteries of the Diamond Mountains, which are said to

have numbered 108 and which flourished greatly under

this august patronage.

For more than a thousand years pilgrims

from China and surrounding countries traveled great

distances to its altars, cutting their names with

infinite labor on the smoothed surfaces of the rocks and

boulders in the valley bottoms, where the only track lay

in the beds of the mountain streams.

Some of these inscriptions date back to the

13th century. In brass-bound chests in some of the

principal halls of worship are still kept books of great

value, printed in Chinese characters from wooden blocks

more than 1,000 years old.

Curzon

Curzon

The 53 Buddhas in Yucheom-sa

Monks Become Outcasts

Then, more than three centuries ago, came

the period in which Buddhism, hitherto venerated and

popular, was rejected, disestablished, and despised,

being prosecuted by the court, whose official creed was

Confucianism, No monk was allowed even to enter the

gates of the capital; and the priests were degraded to

the lowest class of the people and were abandoned by the

population, whose barbarism sought refuge in the rudest

and crudest forms of dernonolatry, Shamanism. and

superstition.

Some of the monasteries were destroyed by

fire: others fell into decay. The survivors. no longer

the haunts of piety and devotion, became pleasure

resorts, which were visited by the upper classes for

purposes of enjoyment, often of the least reputable

kind, while the monks themselves became the outcasts of

society, addicted to lives of combined mendicancy.

depravity. and indolence.

From this cloud the Korean cloister has

never recovered. At the time of my visit its recruits

were, with few exceptions, drawn from the ne'er-do-wells

and wastrels of society, refugees from justice, the

victims of official persecution, pleasure-seekers of

every description, profligates and paupers, destitutes

and orphans—any, in fact, who wanted a safe retreat and

a quiet lif e. Here and there an insignificant minority

preserved the traditions or kept alive the spirit of the

monastic order.

The Koreans Are Confirmed

Sightseers

The seclusion and beauty of these mountain

fastnesses at once attracted immigrants and afforded

them the necessary protection.

No other people on earth, certainly none so

backward in the scale of civilization, is so

passionately addicted to sight-seeing and

pleasure-seeking or so sensitive to the charm of

landscape as the Korean. 'They will travel miles on foot

to climb a pass or see a view, celebrating their arrival

on the crest hy a mild jollification and by the deposit

of a stone or the suspension of a rag in the little

wayside shrine that crowns the summit, or, if they are

sufficiently educated, by the composition of a few lines

of doggerel verse.

To a people with such tastes the Diamond

Mountains have always appealed with an irresistible

fascination. There, in an area only 30 miles long by 20

broad, shut off from the rest of the world and

accessible only by a few mountain passes, are still to

be found more than 40 monasteries, which at the time of

my visit were said still to contain from 300 to 400

monks, as well as a small number of nuns, and lay

servitors to the number of a thousand. [In 1914, after

the Japanese annexation, the numbers were: monks, 443;

nuns, 85.]

They subsisted in the main on mendicancy,

wandering about the country, almsbowl in hand, and—such

is the simplicity or the superstition of the

inhabitants—extracting liberal supplies either for the

endowment of their idleness or the rebuilding and

redecoration of their dilapidated shrines.

The whole situation was a paradox, whether

we contrast the mise-en-scene with the inmates or the

professions of monkish life with its practice.

I have described the Keumkang San as I saw

them in the changing hues of autumn, and this is

generally regarded as the best season; but I believe

that the spectacle in spring, when the valleys and the

hills are carpeted with the bright hues of violets and

anemones. clematis and azaleas, and, above all, with

lilies of the valley, and when the hillsides are ablaze

with spring foliage and rhododendrons, the wild cherry

and flowering shrubs, is not less captivating.

We devoted the day after our arrival at

Chongansa to a march on foot—for no other method of

progression is possible in those regions except a sort

of native chair borne by men—to the neighboring

monasteries of Pakhuam, Pyounsa, Potakam, Makayum,

Panyang, and Yuchonsa.

The march was along the valley bottom, in

or alongside of or across the torrent bed, where a

foothold can onlv be secured by wearing the native

sandal of twisted string, and these have to be changed

every few miles. Pakhuarn was a tiny monastery, with

only three inmates. Pyounsa, with ten, was larger, and

had an abbot, wearing a huge circular hat.

Here was a newly painted temple with a

portentous drum, the size of a small tun, resting on the

back of a monster. There were brilliant paintings on the

walls and a pink gauze veil hung in front of the figures

of Buddha.

As we proceeded upstream the surface of the

rocks was scarred with the incised names of generations

of pilgrims, which must have taken days, if not weeks,

to cut.

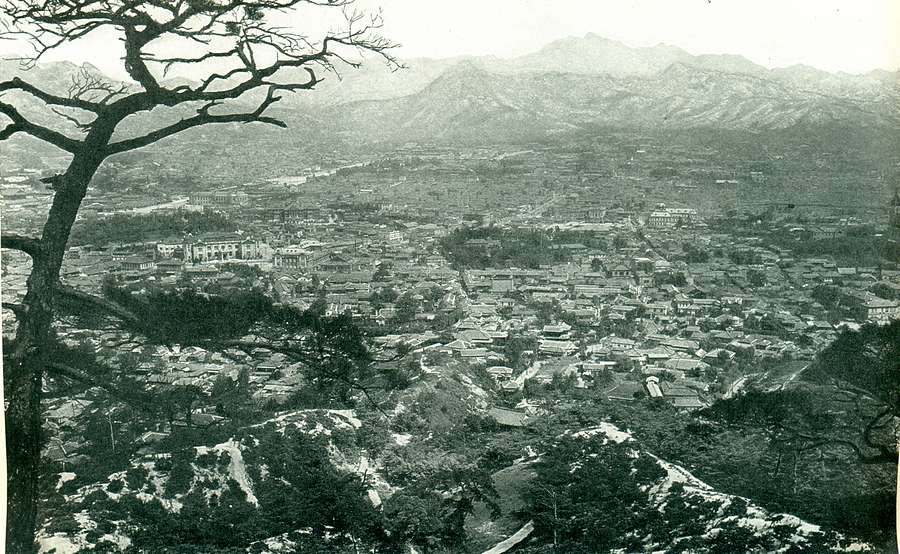

E. M. Newman

E. M. Newman

Seoul (this and the rest of the photos

have nothing to do with the Diamond Mountains)

The Grandest View in Korea

Behind Pyounsa, at the top of the hill

(2,750 feet), is seen the great view of the "Twelve

Thousand Peaks," said to be the grandest in Korea. The

title is merely a quantitative symbol; but if each

pinnacle and cone and spire in that wonderful outlook

were counted, it might be that the total would not be

found too high.

Potakam is not a place of residence, but an

altar to Kwanyin (the Goddess of Mercy), built high up

on a ledge to the right of the valley and supported by

iron girders and a cylindrical shaft or pillar of iron.

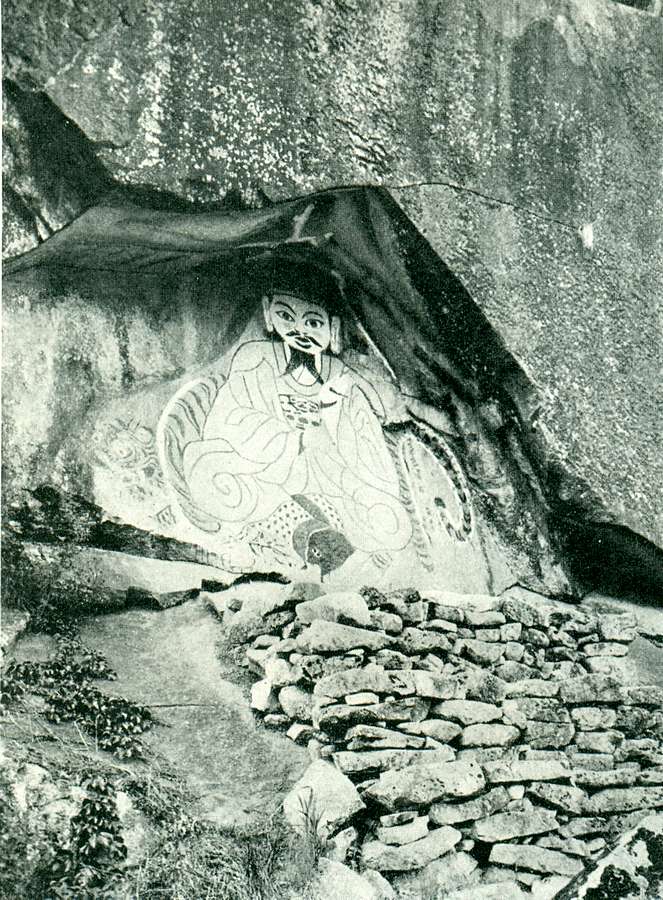

Near Makayum is a colossal image of Buddha, known as the

Myokil Sang, 40 to 50 feet high, sculpted in relief on

the face of the rock, with a small stone altar in front.

The right hand of the figure is raised and

the fingers of thc left are outspread across the breast.

The expression of the countenance is placid and serene.

Near Makayurn is some of the loveliest

scenery in these mountains. There, in a very beautiful

ravine, called Manpoktong, or the Grotto of Myriad

Cascades, is the Pearl Pool, Chinjutam; a neighboring

peak, with a wonderful outline. is Sajapong, the Lion

Peak, and a little farther to the northeast are two

Manrnulsangs, New and Old, which means "Aspect of Myriad

Things," the idea being that the fantastic rocks in

these areas resemble, as they might well be thought to

do, all existing shapes in the world.

Were such scenery to be found in Europe,

thousands of visitors would pour to it from every part

of the Continent.

From here we crossed the watershed by a

very steep climb over the Naimuzairyung Pass, 4,300 feet

above the sea, which is visible from it in clear

weather, and descended upon the small monastery of

Panyang, and the much larger and recently restored

establishment of Yuchonsa.

A great deal of money had been spent here;

and the abbot and his following, of whom 13 monks and 8

lads happened to be home (there are said to be 100 monks

in all), were on a different plane, both of cleanliness

and manners, from their neighbors.

Yuchonsa is now the largest monastery in

the Diamond Mountains and comprises no fewer than 22

buildings. The main temple contained a very elaborate

carved and painted erection or iconostasis, with 53

little images of Buddha, each perched on a little stand

with a silk cloth below, and framed in a

grotesque-colored background, made to represent the

roots and branches of a tree twisted in the most

fantastic convolutions. On either side of this

monstrosity were two great fan-shaped bouquets of

scarlet and white flowers.

A nine-storied pillar or stone pagoda stood

in the court, on the right hand of which were three

temples, with small grotesque seated figures all round,

and fresh paintings on the ceiling.

The guest chambers of this monastery were

the best that we had seen, and we ate our lunch in a

small room with a papered floor, warmed by a flue

beneath.

I have said little about the scenery on

this day's march, which was a total distance of 90 Ii,

or between 25 and 30 miles. But it was as glorious as

any that had preceded it, though the march was much more

fatiguing, a good deal of it being over slippery and

slanting boulders by the torrent side, on which the

traveler could not possibly retain his footing in soled

boots and where he would be helpless without the native

string sandal.

ln parts it is a nasty climb, for the rocks

have been worn smooth by the attrition of pilgrims' feet

for centuries, and just below glimmers many a deep pool.

into which the slightest misstep will send the wayfarer

headlong.

The torrent must further be crossed and

recrossed many times by slender bridges. composed

sometimes of a single pine stem. A further peril arises

from the stepping-stones, consisting of rude boulders,

uneasily perched in the foaming stream and wobbling

under the tread.

The return journey from Yuchonsa to

Chongansa was made by a different route, and we did not

get back till 7 :30 p.m., after a day of 13 hours.

Watch, Knife, and Cash Disappear

After another night at the foot of the

altar whence the smiling Buddha looked down, we packed

up before 6 in the morning to resume our journey to

Seoul. Then it was that my watch and chain and knife and

the whole of my spare cash were found to have

disappeared from under my pillow, where they had been

hidden throughout the night.

A prolonged altercation ensued, in which

everyone, from the abbot downward, took part—indignant

charges on the one side, violent protestations of

innocence on the other.

Over an hour had been spent on this futile

fusillade when it became necessary to act. Accordingly

we announced our intention to take the abbot (who, by

the way, could hardly have been mistaken for an

ecclesiastical dignitary in any country but Korea) with

us to Seoul, and we placed him in the custody of the two

official yamen runners who had been deputed to

accompany our party.

At 7:15 a.m. we were on the road, the

arrested abbot walking sulkily between his guards in the

rear. I can see the swarthy vagabond as I write.

Valuables Found, Abbot Released

We had not proceeded for more than a

quarter of a mile when a shout was heard from behind and

a monk came running after us, holding the recovered

watch and chain and knife in his hand. The cash had, of

course, disappeared.

The abbot was released, and returned to his

peccant flock; but there was no need to offer him the

customary tip, since his followers had thus effectively

anticipated its voluntary presentation. Had we taken him

to Seoul, I tremble to think what might have been his

fate.

From the valley we presently climbed to the

top of the Tanpa Ryong, or Crophair Ridge (so called

because on reaching this point the candidate for the

cloister in olden days was supposed to divest himself of

his locks and to assume the shaven crown). Here is a

magnificent double view—on the one side the entire sweep

of the Keumkang San range, 20 miles in length, the

russet vesture of the foreground leading up to the

bewildering panorama of gray steeples, pinnacles, and

crags, just tipped with a cloud cap on the topmost

spires; on the other side a valley equally as noble as

that we had left, and beyond this the mountains, billow

rolling upon billow for from 60 to 70 miles, till lost

in the blue haze of the horizon.

Next day we rejoined the main road to Seoul

at Changdo; and so ended my never-to-be-forgotten visit

to the monasteries and mysteries of the Diamond

Mountains.

Since the Japanese annexation of Korea the

monasteries have been subjected to strict regulations as

regards their property, their buildings, the choice of

the superior, the tenure of office, ancl the course of

life. There is now an examination for the priesthood;

and I am afraid that if I went back to my former haunts

I should no longer find myself the victim of monkish

thieving or be able to arrest an abbot of Chongansa.

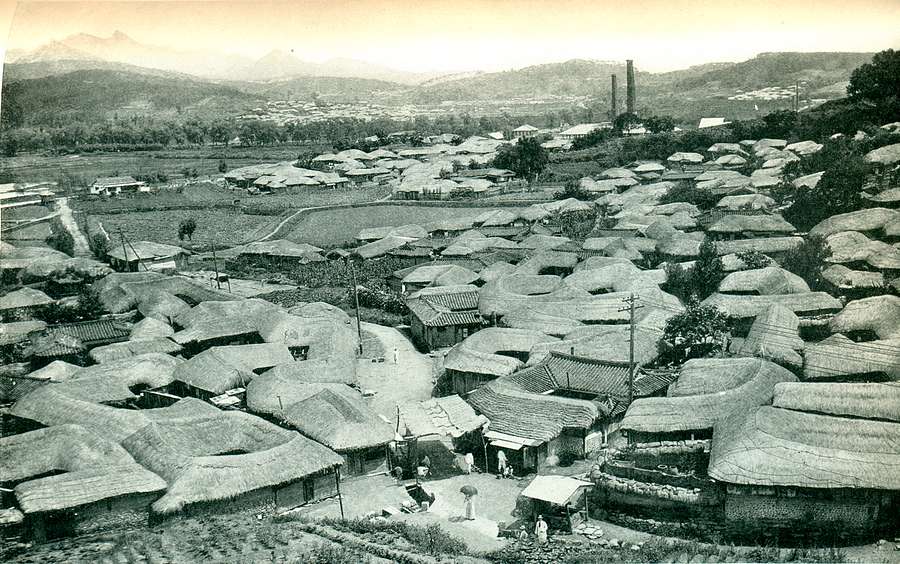

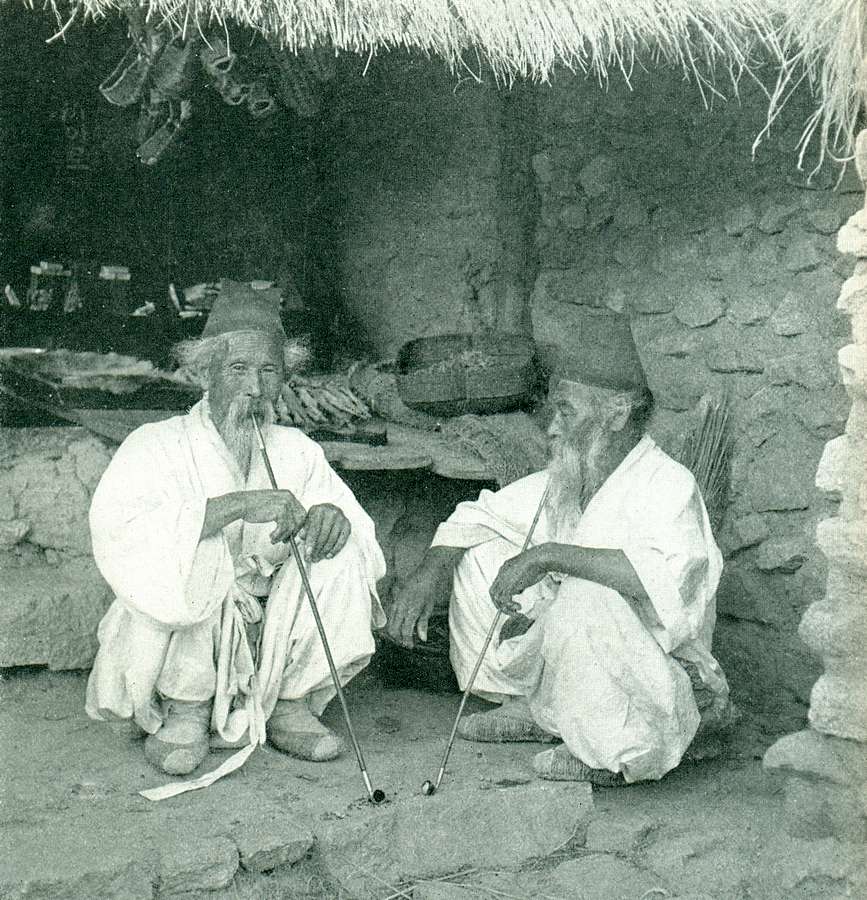

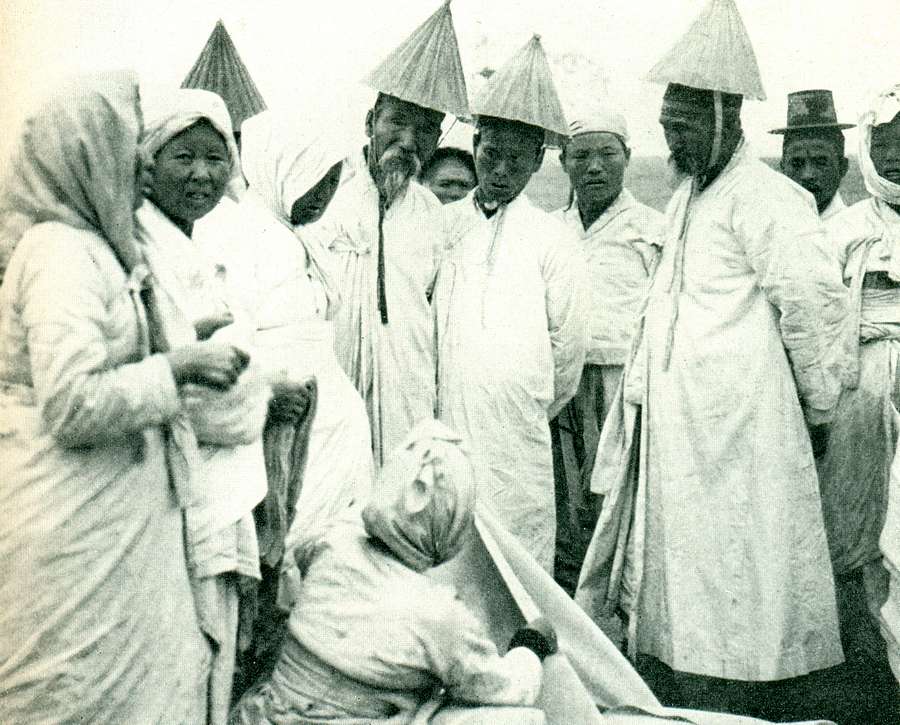

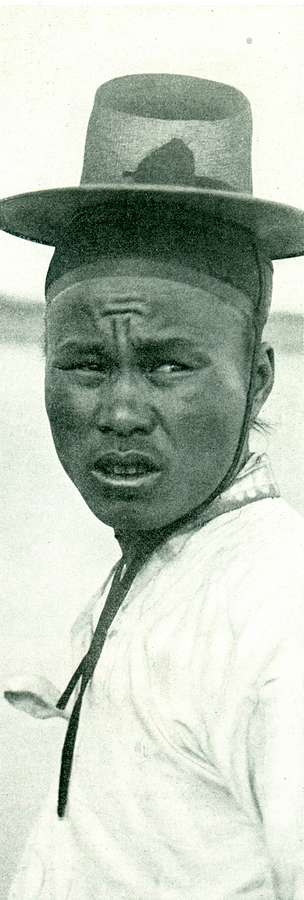

The remaining photos are of

mostly unidentified places and with unknown dates

E. M. Newman

E. M. Newman

Underwood & Underwood

Underwood & Underwood

Underwood &

Underwood

Underwood &

Underwood

In Daegu

Graham Romeyn

Taylor

Graham Romeyn

Taylor

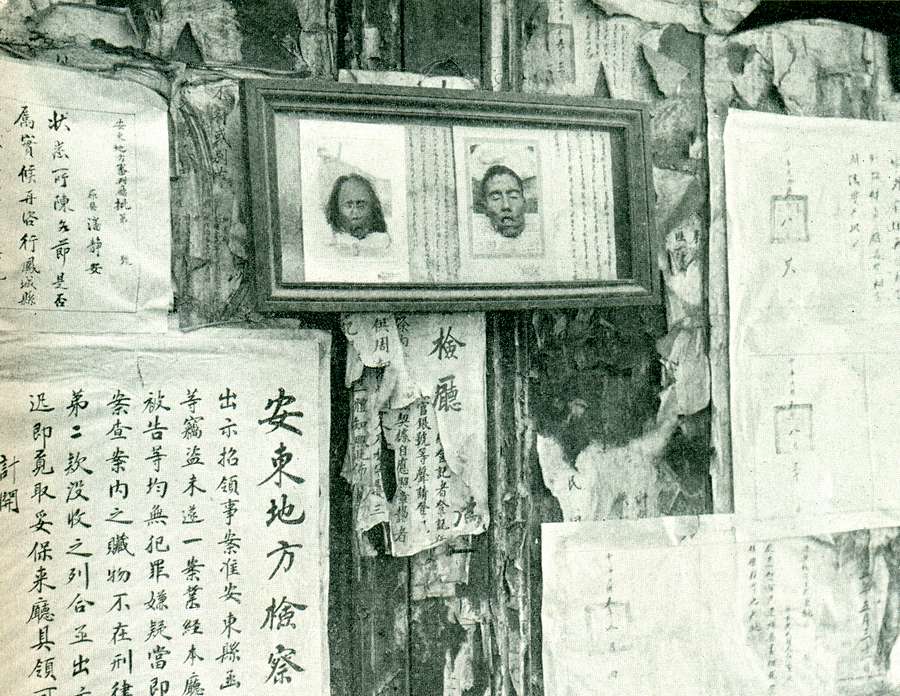

J. B. Millet

J. B. MilletPolice station notice board: Warning, thieves will be beheaded.

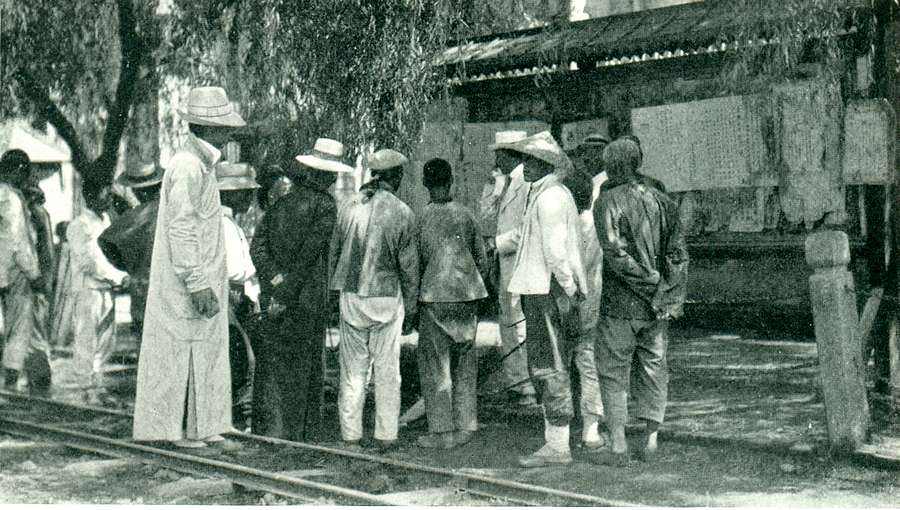

J. B. Millet

J. B. Millet