by Joan S. Grigsby

From: Lanterns by the

Lake (London: Kegan Paul, Trench,

Trubner & Co., Ltd. 1929)

Joan Savell Grigsby and

her husband Arthur Grigsby came to live in Japan in 1924. Most of the poems in Lanterns

by the Lake were written in Japan, about Japanese subjects, but at the last

moment, late in 1928, perhaps hearing of the poet’s plans to move to Korea, the

publishers seem to have asked her to include some poems on Korean topics. The

Grigsbys arrived in Korea in January 1929.

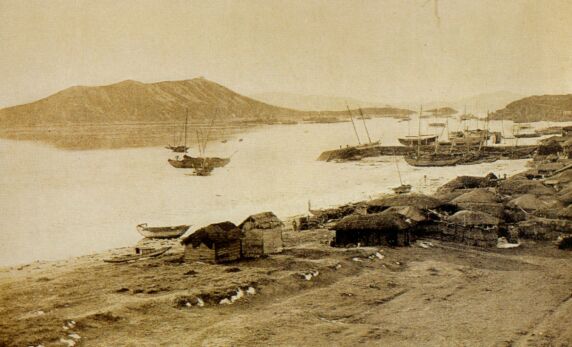

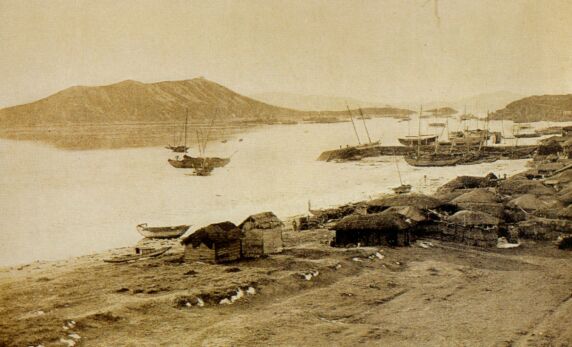

It may be that the boat

from Japan brought them to what is now Inch’ŏn, then known as Chemulpo, which

would explain the location of the first poem, though not its repeated use of

the word “beloved.” Joan Grigsby does not write in her own person so much as in

a variety of more or less dramatized voices. It would also be possible to hear

in this poem someone straining to love what does not look like a very loveable

seascape. The reference to “the swift brown currents swirling” is realistic,

the tides produce very powerful currents in the area.

You will remember these

beloved islands,

The wild acacia thicket,

silver green

After the rain ; the

stone pines on the high lands ;

The swift brown currents

swirling round between

The white sand beaches of

the little islands.

You will remember—there

is no forgetting—

Those orange sails

against the dying day,

When, on the ebb tide,

homeward junks are setting

Across the Yellow Sea to

Wei Hai Wei,

With little winds between

their wet ropes fretting.

And you will dream of the

queer freights they carry—

Globe fish and seaweed,

pigs, perhaps a maid—

Some lovely, slant-eyed

child who sails to marry

Her destined lover,

lonely and afraid,

Part of the cargo any

junk will carry.

Swift is the dusk. Stars

wake above the water.

Deep in the shadow of

acacia trees

Pale lanterns move. The

sound of women’s laughter

Breaks through the

whispered singing of the seas

Then dies. No sound is

left but wind and water.

So shall you dream of

these beloved islands—

Dusk and the stars above

the Yellow Sea,

Wind in the wild acacias

on the high lands.

Departing ship lights.

Such a memory

Shall haunt your heart of

these beloved islands.

Arriving in Seoul in the

depth of winter, in January 1929, they soon moved into the upper floor of an

extraordinary mansion named Dilkusha, situated in a large garden on a hillside

above Seoul. The vast garden round the house could only be reached by climbing

a steep, narrow, crowded, badly paved alley running between small houses. The

sounds reported in this poem, and the emotions they evoke, suggest something of

the poet’s disarray on finding herself transported from the refined, subdued

orderliness of Japan to the uproar of Seoul and its markets. The result is

powerful.

High o’er the twisted

streets and huddled alleys

The white stars tremble and, with night, reveal

The hidden beauty of this

Eastern city—

Dream things that daylight or the gods conceal—

Jealous, perhaps, to

guard some old enchantment

That only starlight and the night reveal.

Out of the narrow lane

below my garden

The sounds of night arise, confused and wild,

Swift throb of

drums, a mourner wailing, wailing ;

Men quarelling ; the sobbing of a child ;

Or women beating

clothes with wooden paddles

Or footsteps wandering, restless, weary, wild.

The white-robed forms

move slowly, crowd together

About a chestnut stall. The brazier’s glow

Lights up black eyes and

hungry, narrow faces

Below the high-crowned hats. They come and go

Wandering, chattering in

darkened alleys

Like ghosts of men forgotten long ago.

Clatter and cry—hoarse

voice of vendors calling

Their wares. The markets open for the night,

Gay china, yellow

oranges, green cabbage

Spread below smoky lamps’ uncertain light,

Amid the ceaseless hum of

surging chatter

That swells and falls upon the Eastern night.

Then—silence, for the

market hours are ended,

Till the stray dogs begin, half starved and wild,

To fight for garbage.

From some hidden hovel

Rises the wailing of a sickly child

And all night long across

the Eastern city

Go footsteps wandering, restless, weary, wild.

The garden surrounding

Dilkusha included in its walls a huge, ancient gingko that is still there, many

other trees, a flowing spring, and a carved stone remaining from the time when

there had been a temple there in Koryŏ times,

The way to the well—how

beautiful it is

At twilight when the

first pale stars appear

Above the garden and the

quince tree seems

Heavy with hidden

centuries of dreams ;

Haunted by footsteps that

of old drew near

The well, before men made

a garden here.

The quince tree by the

well—so old, so old,

The black stem seems a

thing of stone, cold, dead.

Yet the leaves murmur of

forgotten hours

When women who were

beautiful as flowers

Trod this same path, with

bucket poised on head,

Down to the well where

fallen quinces spread

Pale balls among the

long, dew-scented grass,

And poppy petals

scattered points of flame

Upon the path, the green

moss overgrown ;

Or on the broken steps of

rough, grey stone.

Did they too hear the

quince tree, when they came,

Whisper to them some

secret, haunting name?

The way to the well—how

beautiful it is—

Haunted by wandering feet

that cannot stay,

The red brick path by green

moss overgrown,

The scarlet petals

falling on grey stone,

The old, old quince tree,

singing night and day,

Of women like white

flowers who went away.

The references to autumn

might be taken as the work of the poet’s imagination, since almost certainly

these poems had to be written in the late winter and early spring of 1929, to

be sent to the printers in Japan for inclusion in he volume as soon as

possible.

The quinces are yellow

lamps amid red leaves,

Gay festal lanterns that

a faery hand

Hung there at twilight

when the long leaves turned

From emerald to a mass of

crimson flame,

Enchanted fire that

through the dawn mist burned.

Beautiful is morning on

the land

When quinces hang like

lamps among red leaves.

And when the moon of

autumn lights the hills

Silver green are the

quinces in her light,

Like lamps among the

leaves above the well

That mirrors them

entangled with the stars.

See, there a red leaf on

the water fell.

One by one they will fall

through the autumn night.

Tomorrow at dawn the well

will brim with leaves.

The quinces are yellow

lamps amid red leaves.

Tomorrow, when they

ripen, we will go

Gathering them. In

baskets they will lie,

Pale yellow fruit, a

little pitiful

And sad their bare tree

set against the shy.

But we have seen and we

will always know

Their light of festal

lamps at autumn tide.

Soon after they arrived

in Seoul, Faith Grigsby recalls going to watch the arrival down the road from

the north of a great caravan from Mongolia. That event is not mentioned here,

the road is sordid rather than exotic, but two things stand out. First, the

unromantic evocation of the modern traffic, and the symbolic image of the

shabby palaquin carrying one who had been “a courtier to a king,” in which it

is hard not to see a reference to the humiliation of Korea, deprived of its

king and of its independence. Second, we note the poet’s awareness that this

road (leading north from Seoul’s “Independence Gate”) is continental,

international, that Korea is part of the enormous Eurasian landmass, and that

the fabled city of Peking is not so far away.

Between the hills it

winds away—the high road to Peking.

The bullock carts go down

it in a long, unbroken string ;

The ‘rickshas and the

buses, a shabby palanquin,

An old man like a drowsy

god nods wearily within,

Dreaming of days when men

were proud to own a palanquin.

Now motor cars sweep by

him and cover him with dust;

His gold-embroidered

curtains are soiled with moth and rust

And no one asks his

bearers who the rich man is they bring

Through crowds that

throng at twilight the highway to Peking ;

For no one cares that

once he was a courtier to a king.

Now the muleteers come

slowly, riding on their heavy packs,

Small mules, half hidden

by the loads, sweat streaming down their backs.

Ah ! the shouting and the

straining and the pulling as they go,

Beaten when they move too

quickly, beaten when they are too slow,

Like mules on the Peking

highway three hundred years ago.

Beyond the city gateway,

beyond the broken wall,

Where, from the shattered

rampart, great blocks of stonework fall,

Into the purple mountains

the long road winds away.

Do shadows from those

ramparts lean to watch at close of day,

The lights that move and

vanish along the great highway,

As once they watched and

challenged the scout of Genghis Khan

Who rode through these

same mountains down to the River Hahn,

Telling of greater

countries and of a greater king,

Beyond the purple

mountains and the roadway to Peking ?

Maybe that rampart echoed

the song he came to sing.

Ah ! long, grey road you

wind away below the saffron sky,

Luring beyond the city

gate the dreams of such as I

To gateways at your other

end where still the merchants bring

Their painted fans, their

carven jade and many a silver ring

To market down the road

of dreams—the high road to Peking.

Poems such as this and

the one following it suggest that the poet found it difficult to find many

subjects to write poetry about in her new land.

Love made a lotus flower

with seed of stars

And set it in a garden

far away.

I, passing by upon a

summer’s noon,

Gathered the flower and

carried it away.

Cool in my hand the

silken petals lay

And all night long, below

the watchful moon,

I dreamed of love but,

long before the dawn,

The petals faded with the

setting moon.

This is her fan. It holds

her perfume still ;

The frail, flower scent

that lingered in this room

For such a little while.

Amd still, for me, it

holds the strange, dim smile

That hovered on her lips

and in her eyes ;

She who, in ways of love,

was sadly wise—

She the adored, the

unforgettable !

It would be possible to

link this poem to the previous two, but the image of jade pins tossed into the

dust might also be seen as an image of humiliated Korea.

Hairpins of jade and

combs of gold !

Like stars they shine

about thy face

Amid the lustre of thy

hair,

And red pomegranate

flowers are there

To hold the braids in

proper place.

Hairpins of jade in

silken coil

And combs of gold are

very fair.

Yet I would toss them all

away

To watch the wind and

starlight play

A moment with thy

loosened hair !

Ah ! pins of jade—where

are they now ?

Tossed in the dust with

none to care.

The silken braids are

held in place

Upon my heart and there

thy face

Shines like a star from

clouds of hair.

The gingko tree evoked

here is surely the huge old tree in the garden of Dilkusha, identified by the

reference to the spring, and above all to the “carven altar,” a stone remaining

from the temple that had once stood on the site. The reference to “brown, burnt

grass” suggests that the poet had not experienced Korean summer, with its lush

and well-watered vegetation

“There are trees that love and dream, with

the souls of

men or, it may be, of gods.”

Dawn, and the garden

wakes. The gingko tree

Stirs in a dream while

mists of morning shed

Their pallid veil above

the cloud of leaves.

Noontide and throbbing

heat. The branches spread

On brown, burnt grass

their cool, green canopy.

Deep in the Healing Well

their shadows lie.

Sometimes the blue flash

of a magpie’s wing

Shines in the water or a

green leaf drops

Onto the flat, grey rock

above the spring.

Still dreams the tree in

mists of memory.

Once to this carven altar

women came,

Murmuring to the tree

desires unknown,

Their green cloaks in the

starlight glimmering.

And once, at moonrise,

through the garden shone

The crimson light of

sacrificial flame

That burned for dead men

by the gingko tree,

While solemn chant of

white-robed mourners fell,

Like wind among the branches,

on the night,

Broken by beating drum or

tremulous bell.

Still dreams the tree in

mists of memory.

And these green boughs,

like arms, below the sky

Outspreading, seek to

fold the whole earth in,

One with the vision that

their shadow veils ;

To gather up the lonely

souls of men

Into a deeper soul’s

serenity.

For there are trees and

this, ah ! this is one,

More passionate than men.

They love, they know

The hunger in a heart

that asks of life

Always too great a thing

; that seeks to go

Always too far and so

must go alone.

They love, they know and

peace for ever falls

From these great boughs

that still perceive afar,

Beyond the changing sky,

the swerving wind,

Beyond the sunset and the

morning star

A golden city girt with

ivory walls.

There is something

poignant about this glimpse of an entirely Japanese scene in a city that is so

clearly not Japanese in the Grigsby sense of a magic, “faery” land of ancient

beauty. The poet transfers to the elderly woman she sees her own strong

awareness that Koreans are “an alien race” with characteristics evoked in the

second poem, “Korean Night,” quite unlike the sophistication of the Japanese

and the elegant calm of Japanese townscapes.

(A

Japanese Garden in Korea)

The violet veils of

twilight fall.

I resting on your hill,

Look down into your

garden

And hear the streams that fill

Your fountain pool, your

lotus tank,

Your lake so crystal still.

Their silver voices sing

to me

Who rest upon the hill.

I see your servant slowly

wash

The path of smooth-cut stone

And sweep the scattered

cherry leaves

That summer winds have strown.

How cool the water is

that falls

Over the smooth-cut stone,

Down in you garden

beautiful

At dusk for you alone.

I see you blue hibachi

set

Beside the open screen,

The polished, dark

verandah floor,

The yellow mats within,

Your teacup on the table,

Your plate of sugared bean,

You on the silken cushion

set

Beside the open screen.

What do you dream of, all

alone,

Here in this alien place ?

Another garden, far away

?

Some unforgotten face ?

You are so old to dwell

alone,

So full of gentle grace,

You and your garden

beautiful

Amid an alien race.