Lilian May Miller (1895-1943)

The main source of information on Lilian Miller is Between Two Worlds: The Life and Art of Lilian May Miller,

by Kendall H. Brown, Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, CA: 1999. What

follows is based on that, and on other sources of information.

Lilian Miller’s father, Ransford Stevens Miller Jr. (1867-1932) was

born in Ithaca, New York on October 3, 1867. He entered Ithaca High

School from Ithaca Grammar School in September, 1880, graduated in

1884, and entered Cornell University the same year. He graduated A.B.

in 1888. He went to Japan in about 1890 to serve as secretary to the

International Committee of the YMCA in Tokyo. He quickly mastered

Japanese and from 1895 was acting as interpreter to US Legation, Tokyo.

In 1894 he married Lilly Murray of Lockport, N.Y., who had arrived in

Japan as a missionary in 1888. They had two children—Lillian May was

born on July 20, 1895 and Harriet Hartmann on October 2, 1897. By 1898

he was acting as “Japanese secretary” in the American Legation in

Tokyo, having become part of the diplomatic corps by an indirect route.

He served for a time as a member of the Council of the Asiatic Society

of Japan. In 1909 he was called to Washington to become chief of the

Division of Far Eastern Affairs at the State Department.

Lilian began studying traditional Japanese painting

under Kano Tomonobu in 1904, when she was only nine, then in 1907 she

transferred to study under the younger Shimada Bokusen and exhibited

her first work that year. Then, living for the first time in her life

outside of Japan, she graduated from Western High School in Washington,

DC and went to study at Vassar College in New York, where she was a

classmate of the famous poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, graduating in

1917. By that time her father had been serving as American Consul

General in Seoul since 1914, a position he held again after a brief

interruption 1920 - 29. Lilian spent about a year with her parents in

Korea after graduating, then went to work in September 1918 as a

secretary in the Division of Political Affairs at the State Department.

In October 1919 she quit and returned alone

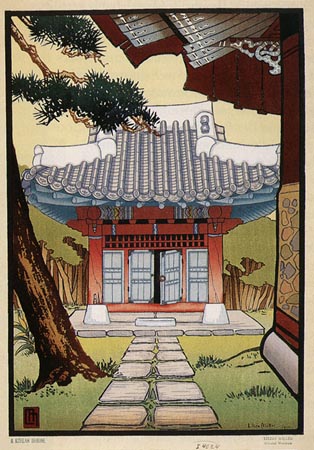

to Japan and to studies with Shimada Bokusen. A painting “In a Korean

Palace Garden” based on a sketch she had made in Korea earned her a

high award at the 1920 Imperial Salon. It was in September 1920 that

she turned to woodblock print production, in part because she needed a

way of earning a living. By 1922, she is said to have produced more

than 6,000 prints and holiday cards, and had figured in a number of

newspaper articles in Japan and the US. Kendall H. Brown stresses the

skill with which she devised a way of self-construction stressing her

dual identity as a modern, liberated, American girl and an oriental

artist entirely devoted to her craft, learned during years of arduous

study under reputed masters.

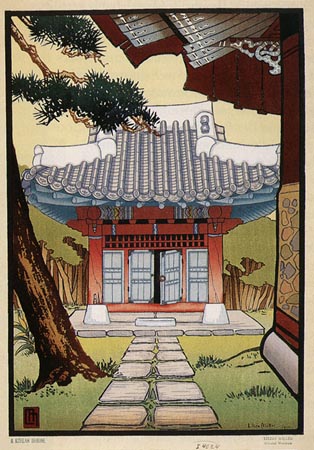

Lilian’s first prints were very largely based on

drawings made in Korea and she went so far as to declare to the San Francisco Examiner

that her mission in life was “to portray the hidden beauty of the

Hermit Kingdom.” Yet Brown argues strongly that in fact her

representations of Korea are weak, Orientalist, stressing the "quaint"

aspects that confirm Japanese representations of Korea as a backward

country whose only hope for development is to become fully part of

Japan. [See a slideshow of her Korean prints] Certainly there is a vast difference between her pictures and

those of Elizabeth Keith who was painting Korean scenes at the same

period in a very different spirit.

On September 1923 Tokyo was largely destroyed by the

great Kanto Earthquake; Lilian was in Seoul on a visit to her parents at the time,

she was safe, but her studio, with her woodblocks, as well as the

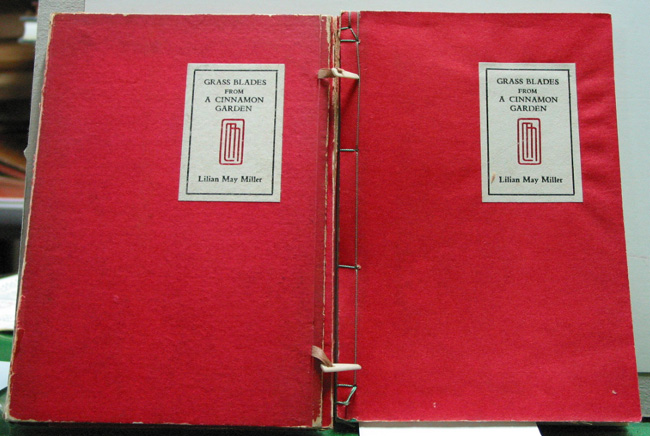

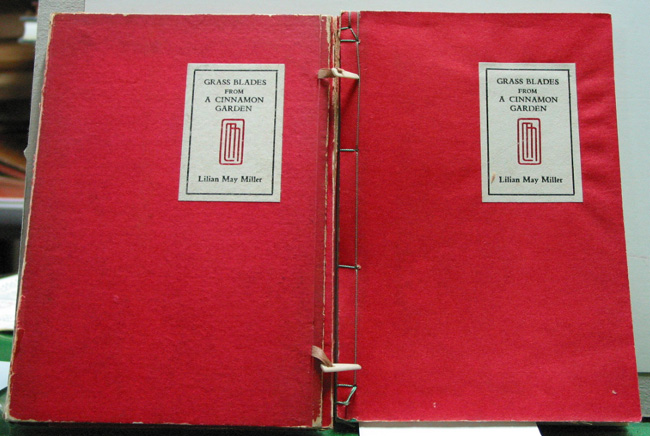

printer’s shop where her book of poems Grass Blades was being

printed, were all destroyed. She then fell seriously ill,

perhaps with beriberi, a vitamin-deficiency disease, and she spent

three years recuperating in her parents’ home in Seoul. In 1927 she was

well enough to publish a revised version of her poetry book Grass Blades from a Cinnamon Garden

and start producing new prints, including re-issues of earlier ones.

Kendall H. Brown stresses the visual quality of many of the poems, and

concludes that while “her poetry was often flat and contrived, her art

was becoming increasingly radiant and natural.” A number of the poems

in the volume are ardent expressions of love addressed, it seems, to

women and Brown notes: “The feminized Orient, alternately maternal and

sexual, is easily linked to the desired lover who is at once the gentle

teacher and the object of amorous desire. Thus, the Orient becomes the

lover and the lover becomes the Orient, both ideal states of grace and

sites of feminine creativity.” (p.25)

Lilian with a Japanese companion. Photo from Faith Norris's Book

Lilian with a Japanese companion. Photo from Faith Norris's Book

As Lilian prepared to make a visit to the United

States late in 1929 to renew contacts with the American art world, she

happened to meet Grace Nicholson (1877 – 1948), who dealt in oriental

antiquities, in Seoul, and this friendship enabled Miller to meet and

make use of many important art contacts on her American trip and

afterwards. During her lectures and exhibitions in America, she dressed

in Japanese style, wearing an elaborate kimono. In 1930, her father

returned to the US and became head of the Far Eastern Department in the

State Department, Washington. Still active in 1931, he died in

Washington in 1932 and another funeral was held in Tokyo in October

1932 when his wife and Lilian took his ashes to be interred in Yokohama

Foreign Cemetery. After that her mother stayed with her in Japan.

During the Depression, Lilian evolved a new style of watercolor that

sold well.

In 1935, she had surgery for a large cancerous tumor, including a

hysterectomy. For a long time, Lilian had been ardently pro-Japanese,

regarding the growing involvement in Manchuria and China. However, in

early 1936, after Japanese radical officers assassinated several

leading politicians, Lilian and her mother left Japan and moved to

Honolulu. There she returned to watercolors, usually working outdoors.

Another relocation in late 1938 to San Francisco may been due to the

larger access it offered to commercial markets. The massive redwoods

and cedars of California reminded her of growing up in Nikko, and she

began to include them in her work.

Undated photo

Undated photo

In the summer of 1941 she and a friend made an adventurous 3-week

hiking trip through southwest Alaska. The Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor in December was a terrible shock to her, she felt betrayed by

the country of her birth and adoption. She signed on with a Naval

counter propaganda branch as a Japanese Censor and Research Analyst.

Late in 1942, she was found to be terminally ill with cancer and she

died on January 11, 1943.

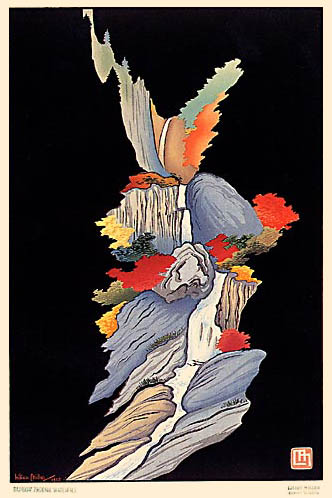

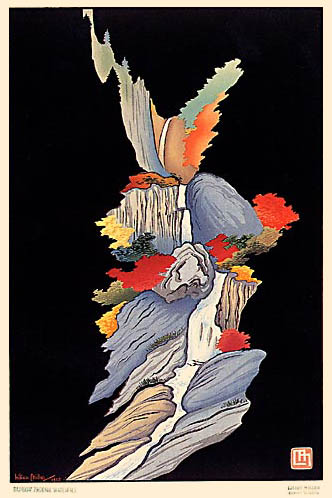

Waterfall: Lilian May Miller

Waterfall: Lilian May Miller

Undated photo

Undated photo